My PhD project is looking at how our current spatial perception of the Alps as a region was built during the Enlightenment and facilitated by the development of networks and routes throughout the Alpine space. One of the key areas witnessing this process, I believe, is the vicinity of Lake Geneva. It certainly lies in a unique location, between Alpine and Jura mountains, and across state borders. It is by all means a borderland, a place of transition between different regions, different topographies, and different societies. As a result, Lake Geneva has always been a particular experience for travellers and explorers. It has challenged perceptions and representations of nature, knowledge, and science. I am currently browsing dozens of British travel accounts expressing the authors' relationship with water, with mountaineering, or au contraire how Rousseau and Voltaire became Lake Geneva's top attractions beyond its extraordinary natural features. However, this article is not meant to be historical. In 2014, Lake Geneva continues to be a crucial space of transnational interactions. Geneva is building its cross-border metropolis, yet transport is once again not up to what one should expect. So we have two transport spotlights today.

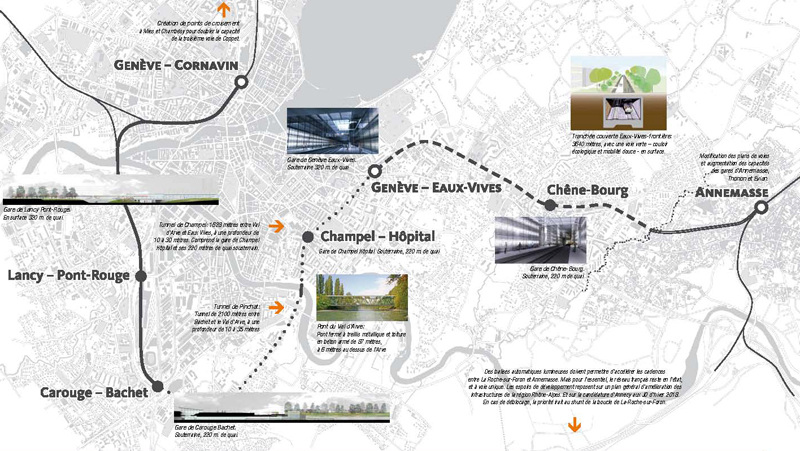

Only a fool would deny Geneva's international and transnational status. I am not even referring to the handfuls of International Organisations based in the UN quarter. More importantly, Geneva is nearly entirely surrounded by French territories. About 70,000 French workers cross the Franco-Swiss border every morning to work in Geneva; considering the current exchange rate, we can assume that as many Genevese do the opposite journey to go shopping in France at weekends. This is the normal balance which you can find elsewhere along the border, near Basel or Neuchâtel. Annemasse (a few miles away across customs) has become the suburb of Geneva. And yet, these two are not linked by a railway. The project, nearly as old as Geneva's membership in the Swiss confederation, has never been finalised. This should finally be operational by the end of this decade. Named CEVA, the railway will link Geneva's main station to its little cousin located in the Eaux Vives neighbourhood (still in Switzerland, but managed by the French railway authorities and used as a terminus for trains from Savoy). Moreover, with the creation of intermediate underground stops, this will create an actual network centred on Geneva but reaching more than 50 cities, towns, villages and neighbourhoods, regardless of which side of the border they are on. The use of regional trains to create high-frequency underground networks in city centres is not new, as you can see in other Swiss cities but also in Paris, London, Glasgow or most German cities. Let's hope fares will remain simple, as the network will spread across different currencies and different transport authorities.

When it comes to Lake Geneva, the question of borders is more alive than ever. While the Franco-Swiss border lies for most parts at the middle of the lake, some of the borderline has been drawn on dry land, which creates all sorts of network-related issues. This is what happened with the Tonkin railway between Evian and St Gingolph. The line between Evian and St Gingolph (which physically exists) is no longer in service and therefore will soon become the only missing railway link around Lake Geneva. Why does this matter so much? Why is it worth comparing it to the very urban CEVA line, whilst the total population along the Tonkin railway is less than 10,000? Well, let's look at the evidence from micro to macro scale. - Located at the foot of the Alps, this region is of course very mountainous. Only one road follows the same route: that road is too narrow and runs through the centre of each town and village, which has of course led to countless deadly crashes, as local newspapers often relate. The hardest part of the job has already been done: there is a railway that only needs to be modernised. This will finally be a safe, eco-friendly and less noisy alternative. Currently stopping right at the border, at the heart of the bi-national town of St Gingolph, most people's lives are not this easily drawable and it is urgent to offer this service again. - For the whole population of the south bank of Lake Geneva (including Geneva itself!), the line will allow a new route to emerge from Geneva (via CEVA) all the way to Canton Valais, famous for its ski resorts, spa towns, and other local curiosities. The Geneva-Lausanne line, on the northern side of the lake, is saturated and it is crucial to offer a sensible alternative for those who would find the southern route more convenient. - This line does not have to be a local one. When put together with the rest of Lake Geneva, it will recreate a truly international network, binding together Geneva's famous airport and exhibition centre, Evian's thermal facilities and world-class golf courses, Montreux's Swiss Riviera, Lausanne's scientific centres, numerous International Organisations, and of course the Alps. A local association is fighting to see the line reopened. You can see their promotional film (still fictional in 2014...) below. My PhD research shows that Geneva was one of the first and most crucial places of interactions for travellers heading towards the Alpine region. When Napoleon was defeated in 1814-15, British travellers rushed back to the Alps, which they had not been able to visit since the end of the previous century. Two places were particularly important in that process: the road from Geneva to Savoy (to allow travellers to reach Chamonix and Mont-Blanc) and the eastern edge of the lake (where foreigners would sail in order to witness the place where Rousseau imagined the story of Julie). Nowadays, both places have evidently lost their top place in Geneva's travel network. Let's hope that an article written in 2020 will revise this statement.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |